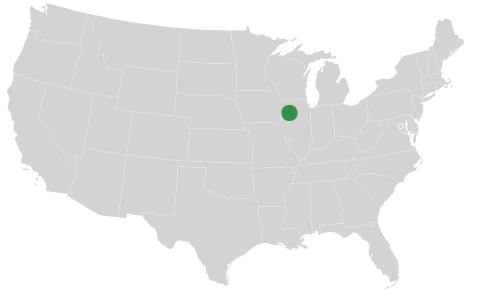

In the summer of 2012 the Continental U.S. faced its worst drought in recent history. Dry conditions across the Midwest decimated many farmers' grain harvests. Illinois farmer Scott Block was among the victims of the drought and suffered severe crop losses, particularly among his corn and soy crops. But thanks to his on-farm composting program, Block found a way to cut his losses in the aftermath of the drought, and in the case of a late planted oat forage, he discovered the potential of compost to increase the yield of forage crops on his farm.

In the summer of 2012 the Continental U.S. faced its worst drought in recent history. Dry conditions across the Midwest decimated many farmers' grain harvests. Illinois farmer Scott Block was among the victims of the drought and suffered severe crop losses, particularly among his corn and soy crops. But thanks to his on-farm composting program, Block found a way to cut his losses in the aftermath of the drought, and in the case of a late planted oat forage, he discovered the potential of compost to increase the yield of forage crops on his farm.

In 2011 Scott Block bought an Aeromaster compost turner and began processing manure and spent bedding from his 840 cow feedlot, where he raises 640 beef cattle along with a 200-head cow and calf herd. Scott's motivations for composting were twofold: He was having challenges keeping up with the large volumes of manure that were created when he expanded his feedlot, and he wanted to become independent of costly commercial fertilizers by transforming his feedlot waste into a powerful, economical, on-farm fertilizer. His goal is to use compost to replace his need for commercial fertilizer all-together. As an unexpected bonus, sales of his high-quality compost are already giving him another way to increase revenue on his farm.

Block applied his first batch of high quality compost in the fall of 2011 on as much cropland as possible. In fact, he completely replaced his commercial fertilizer with one ton of compost for his corn crop, along with some supplemental foliar nitrogen after the corn sprouted. “We actually didn't apply any dry fertilizer last year, we strictly went with one ton to the acre of compost on our corn ground, and then we applied nitrogen later on,” he explained. He also replaced his starter fertilizer with extracted compost tea which he made using the Aeromaster Compost Tea Extraction System, he had purchased from Midwest Bio Systems early in the spring of 2012.

Block admits that it wasn't recommended that he make such a complete transition to compost so quickly, but he explained that he wants his farm to become independent of external inputs as soon as possible, and he noted that until the drought hit, his crops seemed to grow just as well on a full diet of compost, as if they were fertilized with commercial fertilizer. He even noticed more leaves on his corn plants than normal. But then the drought hit, and Block's region of Illinois went without water for weeks on end. At this point all of his crops suffered. “I just didn't get any rain. I was in a severe drought situation,” he explained, emphasizing his major crop losses. But thanks to his compost, even among these severe losses there was a silver lining.

Increasing corn fodder yields

Despite the drought, Scott noticed that compost had a noticeable impact on the health of his corn crop. “We bale our cornstalks quite a bit following our corn crop,” Scott explains. “I've been doing that now for four or five years because I use it (the corn stalks) down here in the feedlot for feed and for bedding. And I was consistently getting four bales to the acre. Until this year. And here I was thinking with drought I would get less,” he chuckled. “I ended up with five bales to the acre of corn stalks... And I knew all year my corn had more leaves and stuff. I think that I did have a healthier and better plant out there and the only thing I can attribute that to is maybe the compost gave me more stalk which in turn would have led to more yield had we got any rain this year.” He adds that if he had rain, he feels that he would have had much better results.

“Of course, everything's gotta have rain,” he said, “I don't care what you do. So as far as my corn and soybean yields seeing a bump in bushels per acre I can't say that this year because of the drought. But I honestly believe I would have had better crops than my neighbors had it rained.” But Block's most exciting yield results came from a fall-planted oat crop that received plenty of fall rains.

Abundant oats help to cut losses

When one of Scott's 150 acre corn fields was appraised and estimated to yield 50 bushels to the acre, as opposed to the 180 to 200-bushel average, he decided to cut his losses and harvest the corn for silage. Half of this field, 75 acres, had been fertilized with commercial fertilizer. The other half, an additional 75 acres, Scott had amended with the high quality compost produced from his feedlot waste.

“After we opted for silage we hated to see that ground out there just doing nothing because we knew we had a lot of compost on it, and we knew the crop that was out there didn't use everything,” he recalled. “So we planted some oats with the idea of baling them maybe in November. That was in August,” Block recalled.

Block's decision to plant oats was well-supported: Oats have been gaining popularity in the Midwest as a late-planted forage crop to follow wheat or other early-harvested crops. They're an attractive forage option due to their low seeding cost, relatively high forage quality, and yields of two to five tons to the acre, according to a publication by Ohio State University. In a trial by researchers at North Dakota State University, a main-season oat forage crop out-yielded corn forage by 0.7 tons to the acre, and it was produced with $40.00 less inputs, demonstrating the potential for oats as a high yielding forage.

And so, in August Block planted this 150 acre field with oats. It wasn't long until he was seeing a boost in growth due to his compost. “We knew right where we stopped spreading, and the oats were 6 inches taller where we put on the compost than where we did not have any compost, on,” he recalled. That six inch difference in growth over 75 acres added up to a lot of extra forage and significantly higher yields. Scott's oats were “just starting to head out” when he harvested them, and he estimates that they had reached a total height of three to four feet, meaning that the field that had been amended with compost, where the oats grew 6” taller, would have increased his per-acre yields by 12.5 to 15 percent!

Scott's compost, applied in the Fall of 2011, was on his field for 10 months. It fertilized his corn crop during the early stages of its growth, and it still had enough potency as a fertilizer to produce oat plants that were 6” taller than plants in the other half of his field that had been fertilized with commercial fertilizer. How is this possible?

Unlike manure and chemical fertilizer, the nutrients in compost are stabilized, and they're released over time, when the plants need them, as opposed to commercial fertilizers that either quickly wash out of the soil or get tied up with other fertilizers/minerals if they're not absorbed by a crop's roots. Other farmers using high quality compost have noticed a huge increase in the growth of hay crops like alfalfa when they switch to high quality compost as a fertilizer.

Scott turns his feedlot waste between 15 to 20 times before it becomes finished high quality compost. Farmers like Brent Webb in Idaho estimate that it costs them less than three dollars per ton to produce their high quality compost. For farmers like Scott Block who are interested in maximizing crop yields on their farms and becoming independent from external inputs, compost as an on-farm fertilizer can help them afford to maximize yields, while maintaining or enhancing the quality of their feed, especially in these difficult economic times.

Are there many forage crops produced where you farm? What other ways could compost be added to forage rotations to enhance yields?

Sources:

http://corn.osu.edu/newsletters/2011/2011-24/oats-planted-late-perhaps-our-most-dependable-forage

http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/archive/streeter/99report/naked_oats_vs_cornsilage.htm

http://hayandforage.com/other-forages/fill-forage-void-summer-planted-oats