When dairy farmer Mark Webb, owner of an 1,800 cow dairy in Idaho, switched from a confined facility to open corrals, he found himself faced with a manure problem, namely far too much of it.

When dairy farmer Mark Webb, owner of an 1,800 cow dairy in Idaho, switched from a confined facility to open corrals, he found himself faced with a manure problem, namely far too much of it.

Webb's strategy to deal with his dairy waste, which consists of both manure and spent bedding, was to haul it onto portions of his 4,000 acres of cropland. After several years of these heavy manure applications, Mark noticed this practice was having a negative impact on the health of his crops, and soil. And the manure was still “piling up,” literally. Webb needed another solution to deal with his manure problem. He thought composting with a mechanical tractor-pulled compost turner might be the answer.

Composting, the process of fast decomposition or disintegration utilizing heat from the decomposition process as well as microorganisms to break down organic matter such as straw or wood chips, into a rich soil-like substance, is a technique that farmers around the world have used for thousands of years. In recent history, experts have combined knowledge of composting principles with modern agricultural technology to create machines that allow farmers to process large volumes of waste materials more quickly and efficiently than ever before.

Mark decided that such a high-tech approach to composting might help him to solve his manure problem, and so three years ago he bought a locally-produced compost turner that he used to process his dairy waste. The results were disappointing.

“It just took forever to go through any manure at all,” Webb said. “The guy just sat on the machine, and we never did make much headway. We didn't even get through it all once, I think, in that year.”

Mark suspected that his machine was inefficient, but when he saw his cousin Brent's Aeromaster Compost Turner, he knew this was the machine that could solve his waste management woes.

“It was eating it up.” The Aeromaster in action.

Mark's cousin, Brent Webb, a neighboring dairy farmer, also beds a large portion of his cows in open corrals and he, too, turned to composting as a strategy to process all the manure from his 1,200 cow dairy. In addition to waste management, Brent wanted to learn how to make “high quality compost,” to rebuild the biological life in his soils, and supplement his commercial fertilizer needs, perhaps completely replacing external inputs from off the farm, some day.

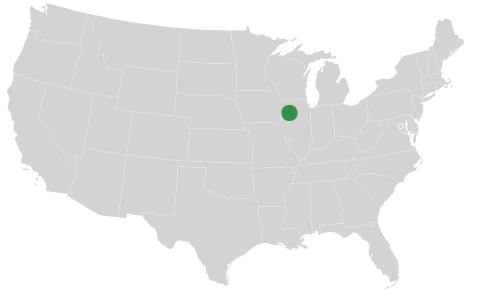

This quest for “the perfect compost” led Brent to a Midwest Bio Systems’ composting workshop where he learned about the “Advanced Composting System,” and saw the Aeromaster compost turner in action. He immediately ordered one of his own and two-and-a-half months later he had produced his first batch of beautiful, high-quality compost.

It wasn't long after seeing Brent's turner in action that Mark ordered one of his own. By August he, too, was composting with an Aeromaster, and by the end of that fall, after eight turnings, he had processed all of his operation's waste, something he had never been able to do before. “That thing was really eating it up!” he exclaimed.

Composting with the Aeromaster

Both Webbs have observed some big differences between Mark's old turner and the Aeromaster. For one, the old turner “pushed” it's way through the compost windrow, rather than actually “turning” the material.

Turning, as opposed to “pushing” material is one of the keys to successful composting. Turning flips and aerates the material in the windrow. It also mixes the materials evenly and helps to create a uniform particle size. This speeds the decomposition process and breaks down their dairy waste, faster.

The Aeromaster also evenly mixes the materials in the windrow, even those on the bottom. By contrast, Mark's old turner left about one foot of material on the bottom on the windrow untouched.

The Aeromaster turner also has a water tank connected to it and sprays every particle with 300% overspray nozzles to moisten the compost during turning to maintain optimum moisture in the pile. Moisture is another important element during the breakdown phase of composting. It also gives the composter a way to inoculate his windrow with beneficial bacteria which also speeds decomposition.

Finding the best size for his compost windrows was another learning experience for Brent. The first year he had his Aeromaster compost turner, Brent decided he wanted to compost his waste material as quickly as possible. He thought large windrows would be the way to do that. “I said 'how big can these rows be?'” he chuckled, claiming that some of his windrows were six feet tall. “Even though it (his turner) went through it, it just took a lot more time,” he recalled.

Brent has since discovered that smaller rows compost more quickly. He now builds windrows that are much smaller than the huge windrows he started out with. These small rows break down faster and after a few turnings he combines two or three windrows, a technique recommended as part of Midwest Bio Systems’ Advanced Composting System. Having smaller windrows is also appealing to Brent because it allows him to drive about “..three times as fast,” he laughed.

Another huge benefit composting brings the Webbs is that it shrinks the volume of their manure to approximately one-third of its original size as it is turned into compost and there's less “water weight.” This means that it takes less trips with a spreader to apply the compost over both of their 4,000 acres of cropland, lowering their fuel costs. The nutrients in compost also become stabilized and more concentrated than in raw or partially decomposed manure, so the amendment that the Webbs are spreading on their fields gives them more benefit from their manure for less effort. Now, Brent said, “Rather than trying to get rid of it, we're looking at it as an asset. And we're trying to enhance that asset (through composting).”

Efficient composting equipment has made all the difference on the Webbs' farms. Yet more efficient processing of manure is not the only benefit the Webbs have gained from their composting program. In the next post we'll explore how they're using composting to create a high-quality fertilizer using only ingredients from the farm, to become independent from external inputs.

How much dairy bedding piles up on your farm? What options have you considered for waste management?